Modern DNS Applications: Powering Today's Cloud and Container Ecosystems

The Role of DNS in Modern Cloud and Containerized Architectures

DNS is no longer just a simple address book for the internet. In today's cloud-native world, DNS plays a critical role in enabling highly scalable, dynamic, and distributed systems. From cloud platforms like AWS and Azure to Kubernetes-based container ecosystems, modern DNS solutions are foundational to service discovery, traffic routing, load balancing, and application resilience.

In this edition, we'll explore how DNS has evolved to meet the needs of cloud computing and containerized architectures. You'll learn about DNS in Kubernetes clusters, DNS-driven service discovery for microservices, DNS-based load balancing across multi-cloud environments, and best practices for ensuring DNS performance and security in modern infrastructure.

Whether you're building applications in the cloud, managing Kubernetes environments, or designing multi-region deployments, understanding the power of modern DNS is essential. Let’s dive into how DNS is shaping the future of cloud and container ecosystems.

DNS in Kubernetes Environments

In Kubernetes, DNS is not just a network convenience — it’s a core building block that enables service discovery, communication between microservices, and dynamic application scaling.

As containers are ephemeral and IP addresses change frequently, Kubernetes abstracts service discovery through DNS, ensuring applications can reliably find and connect to each other.

How Kubernetes DNS Works

When a Kubernetes Service is created, the cluster automatically creates a DNS entry for it. Pods and other services can then access it using a standard DNS name, without worrying about underlying IP addresses.

The DNS naming convention typically follows:

<service-name>.<namespace>.svc.cluster.local

For example, a service named orders in the production namespace would have the DNS name:

orders.production.svc.cluster.local

Kubernetes deploys an internal DNS server (most commonly CoreDNS) as a Deployment inside the cluster. All pods are configured to use CoreDNS as their DNS resolver by default.

CoreDNS in Kubernetes

CoreDNS is the default DNS server for Kubernetes clusters.

It provides:

Service Discovery: Resolves internal services and endpoints

Upstream DNS forwarding: For queries outside the cluster

Load balancing: Distributes requests among healthy endpoints

Caching: Reduces external DNS traffic and speeds up resolution

Customization: You can extend it with plugins (e.g., rewrite, redirect, metrics)

The CoreDNS config is managed through a ConfigMap (coredns in the kube-system namespace).

Example CoreDNS ConfigMap:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: coredns

namespace: kube-system

data:

Corefile: |

.:53 {

errors

health

ready

kubernetes cluster.local in-addr.arpa ip6.arpa {

pods insecure

fallthrough in-addr.arpa ip6.arpa

}

forward . /etc/resolv.conf

cache 30

loop

reload

loadbalance

}

DNS for Headless Services

Normally, Kubernetes Services have a ClusterIP that hides individual pods.

However, Headless Services (ClusterIP: None) allow DNS to return individual pod IPs instead of a virtual IP.

This enables direct pod-to-pod communication and use cases like:

Stateful applications (e.g., databases, queues)

Applications needing to know all pod addresses (e.g., Cassandra, Elasticsearch)

When querying a headless service, DNS returns a list of A/AAAA records — one for each pod behind the service.

Example:

nslookup my-db-service.default.svc.cluster.local

returns:

Name: my-db-service.default.svc.cluster.local

Addresses: 10.244.1.5

10.244.2.7

10.244.3.9

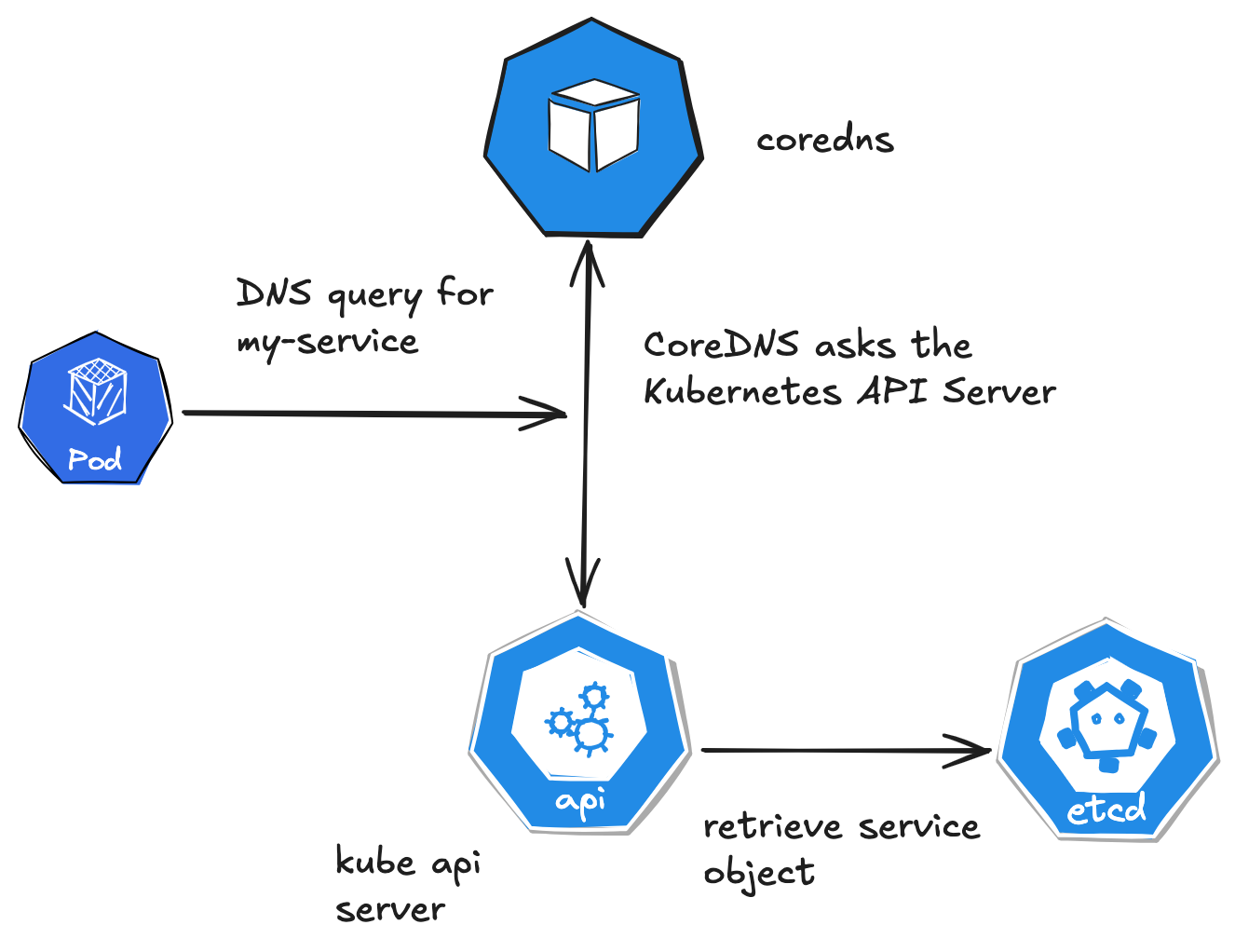

Let’s say a pod in my-namespace tries to resolve my-service:

Pod sends a DNS query for my-service to 10.96.0.10 (CoreDNS ClusterIP).

The query is routed to a CoreDNS pod in kube-system.

CoreDNS appends my-namespace.svc.cluster.local (from search domains) to form my-service.my-namespace.svc.cluster.local.

CoreDNS queries the Kubernetes API and finds my-service with ClusterIP 10.100.1.1.

CoreDNS returns 10.100.1.1 to the pod.

The pod uses 10.100.1.1 to connect to the service.

Troubleshooting Tips

Check CoreDNS Pods: kubectl get pods -n kube-system -l k8s-app=kube-dns to ensure CoreDNS is running.

Inspect Logs: kubectl logs -n kube-system -l k8s-app=kube-dns for DNS errors.

Test Resolution: Use a temporary pod with nslookup

kubectl run -it --rm debug --image=busybox -- nslookup my-service.my-namespaceVerify Pod DNS Config: kubectl exec <pod> -- cat /etc/resolv.conf.

Check CoreDNS Config: kubectl get configmap coredns -n kube-system -o yaml for custom settings.

DNS resolution in Kubernetes involves pods sending queries to CoreDNS via the cluster’s DNS service IP.

CoreDNS resolves service, pod, and external names by querying the Kubernetes API or upstream DNS servers, leveraging search domains for short names.

The process is seamless for most workloads, with CoreDNS handling caching, headless services, and StatefulSets efficiently. Custom DNS policies and configurations offer flexibility for advanced use cases.

Challenges with DNS Inside Kubernetes

While Kubernetes DNS is powerful, it can encounter challenges:

DNS Caching Issues: Applications caching DNS results can cause stale IPs when pods are rescheduled.

Slow DNS Resolution: Large clusters or high query rates can overwhelm CoreDNS without tuning.

CoreDNS Bottleneck: If CoreDNS pods are not highly available or not properly scaled, DNS outages can impact the whole cluster.

External Resolution Latency: Poorly configured upstream resolvers can slow external DNS lookups.

Best Practices for Kubernetes DNS

Deploy multiple CoreDNS replicas for high availability

Use readiness probes on CoreDNS pods to detect unhealthy DNS services

Tune caching settings to reduce load (e.g., increase

cacheTTL for stable services)Monitor CoreDNS metrics with Prometheus for DNS query errors and latencies

Scale CoreDNS horizontally if DNS query load increases

Test DNS Failures to validate resilience (e.g., simulate CoreDNS pod crash)

DNS-Based Load Balancing

DNS-based load balancing distributes traffic across multiple endpoints by returning different IP addresses in response to DNS queries.

This approach offers a simple yet effective way to distribute load and improve availability without requiring additional proxies or load balancers in the request path.

Types of DNS-Based Load Balancing

Several DNS-based load balancing approaches are commonly used:

Round-Robin DNS: The simplest form, where multiple A/AAAA records with the same name are defined, and DNS servers rotate through these addresses in responses. This provides basic load distribution but doesn't account for server health or capacity.

Weighted Round-Robin: An extension of round-robin where different weights are assigned to different endpoints, allowing more traffic to be directed to servers with higher capacity.

Geolocation-Based Routing: Directs users to different endpoints based on their geographic location, reducing latency by sending users to the nearest datacenter.

Latency-Based Routing: More sophisticated than geolocation routing, this approach measures actual network latency to different endpoints and directs users to the endpoint with the lowest latency.

Health-Check Based Routing: Continuously monitors endpoint health and automatically removes unhealthy endpoints from the rotation.

Several technologies enable DNS-based load balancing:

Cloud Provider Solutions:

AWS Route 53 offers various routing policies including simple, weighted, latency-based, geolocation, and failover routing

Azure Traffic Manager provides priority, weighted, performance, and geographic routing

Google Cloud Load Balancing includes global load balancing with health checking

CDN Providers:

Cloudflare, Akamai, and Fastly offer DNS-based traffic management with advanced routing capabilities

Specialized DNS Services:

NS1, Dyn, and UltraDNS provide sophisticated DNS-based traffic management

Open-Source Options:

PowerDNS with dnsdist

BIND with response policy zones and views

CoreDNS with custom plugins

Advantages of DNS-Based Load Balancing

DNS-based load balancing offers several benefits:

Simplicity: No additional proxies or load balancers in the request path.

Global Scale: Can distribute traffic worldwide with minimal infrastructure.

Cost-Effectiveness: Often less expensive than maintaining load balancers in multiple regions.

Reduced Latency: By directing users to nearby servers, overall latency can be reduced.

Limitations and Challenges

DNS-based load balancing also has some limitations:

Caching Effects: DNS caching can delay the impact of routing changes.

Limited Granularity: Load balancing occurs at the DNS resolution level, not per request.

Client-Side Behavior: Some clients may cache DNS results beyond the specified TTL.

Limited Session Stickiness: Maintaining session affinity can be challenging with DNS-based approaches.

Best Practices for DNS-Based Load Balancing

To effectively implement DNS-based load balancing:

Set appropriate TTL values based on how quickly you need to respond to changes

Implement comprehensive health checking for all endpoints

Monitor DNS query patterns and endpoint load distribution

Consider combining DNS-based load balancing with other approaches for different layers of your application

Test failover scenarios regularly to ensure they work as expected

Implement proper monitoring to detect and respond to routing issues quickly

Split-Horizon DNS for Multi-Environment Setups

Split-horizon DNS (also known as split-view or split-brain DNS) is a configuration where a DNS server provides different answers depending on the source of the query.

This approach is particularly valuable in multi-environment setups where internal and external users need different DNS responses for the same domain names.

Common Use Cases

Split-horizon DNS is commonly used in several scenarios:

Internal vs. External Access: Providing internal IP addresses to users on the corporate network while giving external IP addresses to internet users.

Development/Testing Environments: Directing internal users to development or staging environments while external users access production.

Multi-Region Deployments: Routing users to different regional deployments based on their location or network.

Cloud Migrations: During migrations, internal users might be directed to new cloud resources while external users still access on-premises systems.

Privacy and Security: Exposing only necessary services to external users while providing full access internally.

Implementation Approaches

Several methods can be used to implement split-horizon DNS:

Multiple View Configurations: DNS servers like BIND support "views" that provide different responses based on the client's source address.

Separate DNS Servers: Maintaining separate internal and external DNS servers, each with their own zone files.

Cloud Provider Solutions:

AWS Route 53 Private Hosted Zones for VPC-specific DNS

Azure Private DNS Zones

Google Cloud Private DNS

Conditional Forwarders: Configuring DNS forwarders to direct specific queries to different authoritative servers based on the query source.

Technical Considerations

Implementing split-horizon DNS requires careful planning:

Zone File Synchronization: When using separate servers, maintaining consistency between internal and external zone files is crucial.

SOA Record Management: Each view or zone should have appropriate SOA records with independent serial numbers.

DNSSEC Considerations: Split-horizon configurations can complicate DNSSEC implementation, requiring careful key management.

DNS Resolver Configuration: Client systems must be configured to use the appropriate DNS resolvers to get the correct view.

Challenges and Best Practices

Split-horizon DNS introduces some challenges:

Configuration Complexity: Managing multiple views or servers increases configuration complexity.

Troubleshooting Difficulties: Issues can be harder to diagnose when different users receive different DNS responses.

Consistency Management: Ensuring changes are properly propagated to all views or servers requires careful process management.

To address these challenges, consider these best practices:

Document your split-horizon architecture thoroughly

Implement automation to ensure consistent updates across all views

Use DNS management tools that support split-horizon configurations

Test DNS resolution from both internal and external perspectives

Implement monitoring that checks resolution from multiple vantage points

Consider using version control for DNS configurations

Establish clear processes for DNS changes that affect multiple views

If you found this newsletter valuable, consider becoming a paid subscriber to unlock even deeper insights, advanced tutorials, and exclusive content. Your support helps me keep creating high-quality resources for the community.