Stacked vs External etcd:The Production Decision Nobody Explains

Why kubeadm’s default isn’t what you’ll find in production—and when it actually matters.

When you bootstrap a Kubernetes cluster with kubeadm init, it makes a choice for you: stacked etcd topology. The etcd database runs directly on your control plane nodes, right alongside the API server.

Simple. Clean. Done.

But scroll through any serious production cluster documentation—financial services, large-scale SaaS, or anything with “five nines” in the SLA—, and you’ll find something different: external etcd clusters running on dedicated nodes.

Why? And more importantly, does it matter for your cluster?

Let’s break it down.

What’s Actually Different

Stacked etcd puts everything on the same nodes:

Control Plane Node 1:

├── kube-apiserver

├── kube-scheduler

├── kube-controller-manager

└── etcd ← lives here too

Each control plane node runs its own etcd member. Three nodes, three etcd members, one cluster. The API server talks to its local etcd instance.

External etcd separates concerns:

Control Plane Nodes (x3): etcd Nodes (x3):

├── kube-apiserver └── etcd member

├── kube-scheduler

└── kube-controller-manager

The API servers connect to the etcd cluster over the network. Six nodes minimum instead of three.

Simple difference. Significant implications.

The Failure Domain Problem

Here’s what keeps SREs up at night with stacked topologies:

When a control plane node dies in a stacked setup, you lose two things simultaneously:

A control plane instance (API server, scheduler, controller-manager)

An etcd cluster member

These are now the same failure domain.

With 3 nodes, you can lose 1 and maintain quorum. Lose 2, and your entire cluster is down—not just degraded, but down. The API server can’t function without etcd.

External etcd decouples this. Lose a control plane node? Your etcd cluster is unaffected. Lose an etcd node? Your control plane keeps serving (from healthy etcd members). You’ve created two independent failure domains that can degrade gracefully.

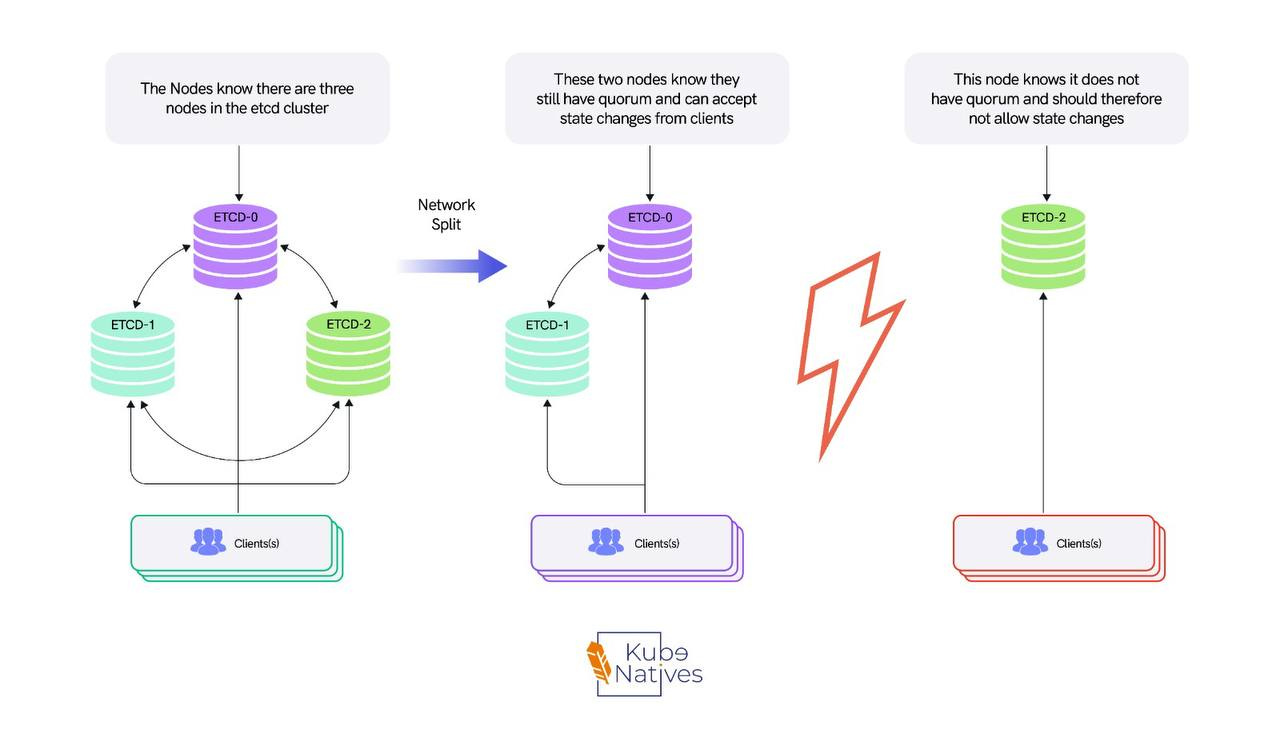

The Quorum Math

etcd uses Raft consensus. Quick refresher on why cluster sizing matters:

Quorum = (n / 2) + 1

Cluster Size Quorum Needed Failure Tolerance 3 nodes 2 1 failure 5 nodes 3 2 failures 7 nodes 4 3 failures

With stacked etcd, your etcd failure tolerance equals your control plane failure tolerance. They’re locked together.

With external etcd, you could theoretically run 3 control plane nodes with a 5-node etcd cluster—giving your data layer more resilience than your compute layer.

(Whether you should do this is a different question.)

The Real Production Concerns

Beyond failure domains, here’s what actually drives the external etcd decision:

1. Disk I/O Isolation

etcd is extremely sensitive to disk latency. The official recommendation is fsync latencies under 10ms. On a shared node, your API server is competing for the same disk—especially during heavy kubectl apply operations or controller reconciliation loops.

External etcd means dedicated SSDs. No contention. Consistent performance.

2. Independent Scaling

Large clusters (1000+ nodes) generate massive etcd load. Every pod, every secret, every configmap—it all lives in etcd. With external topology, you can:

Add more etcd nodes

Upgrade etcd independently

Tune etcd specifically without touching control plane nodes

3. Upgrade Flexibility

Upgrading Kubernetes with stacked etcd means upgrading etcd at the same time. Sometimes that’s fine. Sometimes you hit an etcd version incompatibility or want to test the upgrade in stages.

External etcd lets you upgrade the control plane and etcd cluster separately. More moving parts, but more control.

So Which Should You Choose?

Choose Stacked if:

You’re running dev/staging environments

Your cluster is under 100 nodes

You don’t have dedicated infrastructure engineers

Cost is a primary concern (3 nodes vs 6)

You’re using kubeadm and want the simplest path

Choose External if:

This is a production cluster with SLA requirements

You’re running 500+ nodes

etcd performance issues have already appeared

You need independent upgrade cycles

You’re building a multi-tenant platform

The honest answer for most teams: Start with stacked. It’s not a bad topology—it’s the pragmatic topology.

Monitor your etcd metrics

(etcd_disk_wal_fsync_duration_seconds, etcd_server_slow_apply_total).

If you start seeing latency spikes or your cluster grows past a few hundred nodes, then plan the migration to external.

Premature optimization in infrastructure is just as real as in code.

The Migration Reality

One thing nobody mentions: migrating from stacked to external etcd is non-trivial. It’s not a “flip a flag” operation. You’re essentially standing up a new etcd cluster and migrating data.

If you know you’ll need external etcd eventually, starting there might save you a painful migration later. But “eventually” is doing a lot of work in that sentence.

Quick Reference

Aspect Stacked External Minimum nodes 3 6 Failure domains Coupled Decoupled Setup complexity Low (kubeadm default) High (manual) etcd upgrades With K8s upgrade Independent Disk I/O Shared Dedicated Best for Dev, small prod Large scale, strict SLA

Bottom Line

The stacked vs external decision is really about answering one question:

At what point does operational complexity pay for itself in reliability?

For a 50-node cluster running internal tools? Stacked is fine. You’re not Google.

For a 2000-node cluster running customer workloads with four-nines SLA? External etcd isn’t optional—it’s table stakes.

Know your scale. Know your SLA. Choose accordingly.

Next week: What actually breaks in etcd clusters—and the debug commands that save your 3am pages.